As slogans go, “If you don’t know, Vote ‘No’” is brilliant. Diabolical, yes, but perfect.

The Voice to Parliament debate has been something considerably less than a stirring moment of national self-reflection and reckoning. Outside of the meta-battles about the asymmetrical misinformation-warfare that is in all likelihood going to sink Yes, we’ve mostly had opponents of the Voice arguing against it on the basis that the body it creates would have - gasp! - actual power, while its defenders assure us that, don’t worry, it won’t have any real power at all. The only people actually talking about the assertion of sovereignty are the people opposing the Voice from the Left.

Against that backdrop, “If you don’t know, vote ‘No’” cuts through. It’s neat, clear, and being what Kant called a hypothetical imperative (‘if x, do y’), it tells you what to do. It’s catchy, it rhymes. Quick, name one phrase you remember from the OJ Simpson trial? Exactly.

Of course, the No campaign’s slogan folds like wet cardboard upon even a moment’s interrogation. The retort is thuddingly obvious: “If you don’t know, find out.” Since when has ‘not knowing’ been good enough? But that misses the point of the slogan. It authorises incuriosity, and alchemises ignorance into prudence. It trades in the most valuable commodity the contemporary Right has in its treasury: permission not to care.

But the slogan also works because it taps into a very deep cultural reflex, one that surfaces in all sorts of unexpected places. As certain voices rushed to defend Ben Roberts-Smith, after a Federal Court judge ruled that Roberts-Smith had committed war crimes including multiple murders, it seemed fair to ask why those commentators weren’t outraged that Roberts-Smith had apparently lied to them.

Yet they are simply drawing on some very old muscle memory here. Politely pretending to believe people who deny unlawful killings is something we started doing a long time ago in this country.

More than half a century has passed since WEH Stanner’s 1968 Boyer Lectures in which he coined the term the “Great Australian Silence.” Australian society, Stanner declared, was in thrall to “cult of disremembering” that erased the realities of invasion and violent dispossession from the record. A history of murder and theft was papered over with jaunty tales of convicts, sheep and gold.

This silence was strategic from the outset. Even when Whitehall insisted that ‘Protectors of Aborigines’ be appointed with a remit that included bringing those responsible for frontier massacres to account, colonizers who murdered First Nations people knew that they had little to fear from the authorities. The Protectors always arrived on the scene too late, and curiously, nobody ever seemed to know anything.

Even if the perpetrators could be caught, Aboriginal witnesses could not testify in court on the grounds they were “heathens.” If they cannot give evidence under oath, how can we possibly know what happened?

This feigned epistemic helplessness is remarkably useful, not just on First Nations issues but across a range of political domains. The corollary of the Great Australian Silence is what we might think of as the Great Australian Bewilderment. We pretend not to see what the problem is, and then mime confusion at everyone else’s outrage.

Performative befuddlement runs up and down the levels of government, in the minor side-shows as much as the main acts. Consider the sight of (now former) Victorian MP Tim Smith, at a press conference he’d called to apologise for driving drunk and crashing his Jag into a fence, blustering with indignation at being asked if he’d ever taken drugs. “I’ve never taken a drug in my life!” Tim Smith holds a Masters degree from the University of Melbourne and spent time at the London School of Economics, and has spent his working life in and around government. He surely knows by now that there is no metaphysical or moral difference between the things that fall into the confected category ‘drugs’ and the things (alcohol, caffeine) he puts into his body at dinner parties. But Smith - a man who has spent years thinking about public policy every day as his job - is obliged to not know that, precisely because he can’t allow himself to fall into the same category as people who use drugs.

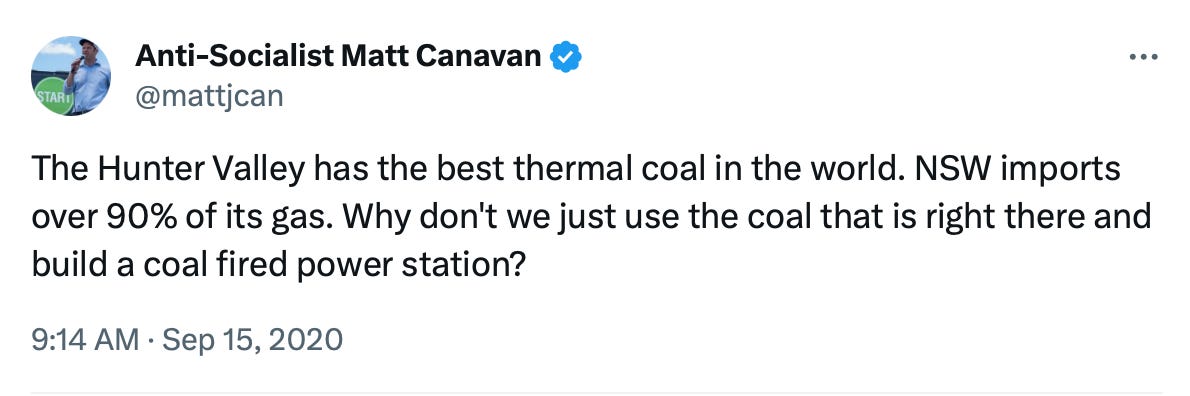

Senator Matt Canavan is perhaps the most obvious example of this studied obliviousness, not because he is particularly good at it, but because he uses the technique frequently and with dismayingly little guile. Whether the topic is coal (it is very often coal):

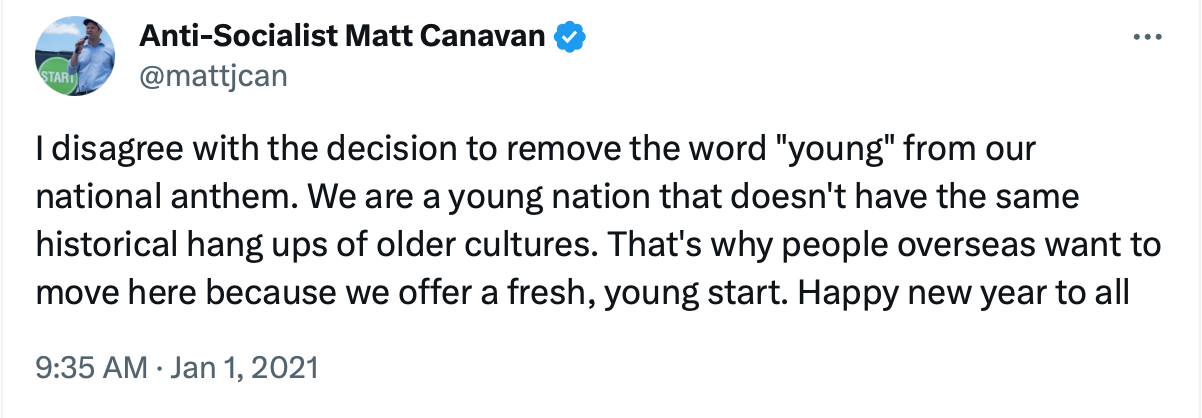

or the problem with calling Australia ‘young’ in the national anthem:

Canavan acts as if he simply can’t imagine why anyone would see any problem with what he’s saying. I mean, it’s not like there’s anything wrong with coal, right? Naturally, this generates the outraged reaction it’s meant to, which is the only metric that really matters here. It is only a slight exaggeration to say this is Canavan’s whole schtick. He’s a one-trick pony whose one trick is pretending not to know what the fuck is going on.

These are rhetorical moves that we’ve allowed to take root in our discourse, partly through not calling them out when they appear, but mostly through a political culture devoid of consequences no matter what the political class say or do. That’s how we find ourselves in the thick of a debate where one side is trying desperately not to scare the horses, while the other side is arguing from, and for, a position of self-aware ignorance.

Predictably, the referendum campaign has furnished us with an endless parade of people pretending not to see the problem with saying the Voice is “divisive” or sets up one group of “Australians” for “special treatment.” To seriously not see why this is a problem, you would need to not know some very basic things about the society you live in. In particular, you would need to not know how that society came into being.

Consider how the Opposition Leader, Peter Dutton, talks of the Voice as ‘re-racialising the Constitution.’ The language is very deliberate. It implies that the Australian Constitution, and by extension the political entity it creates, is at bottom a non-racist document that in the past just happened to have have some unfortunate but inessential racist elements mixed in. The 1967 referendum, and extra-constitutional reforms such as the dismantling of the White Australia policy, excised the racist bits and allowed Australia to achieve, on this telling, a race-blind liberalism that was there all along. Edmund Barton’s insistence that there was no equality between “the Englishman and the Chinaman” and Alfred Deakin’s claim that all Australian politicians were united in “the unalterable resolve that the Commonwealth of Australia shall mean a ‘white Australia’, and that from now henceforward all alien elements within it shall be diminished” were, it is implied, detachable from the polity these men created, and the document that structures it.

We know the truth, of course, whatever we pretend. The problem is in the foundations, not the furniture. The Constitution of Australia creates a state on somebody else’s unceded land, asserting authority over other nations that this state does not even acknowledge let alone treaty with, all in the name of an inherently illegitimate source of sovereign authority (hereditary monarchy). The Voice doesn’t fix that, of course, and First Peoples can and should decide for themselves if they want to be in the colonizer’s constitution at all. Those like Senator Lidia Thorpe who favour a Treaty-first approach are often told this would be strategically impossible, but such an approach might at least have made it harder for white Australians to pretend that the Voice is about “Aboriginal Australians” getting some sort of race-based privileges, rather than the right of the other nations of this continent to determine their own relationship to the Settler-Colonial state.

But right now it’s the Voice that we have to vote on. I will be voting ‘Yes,’ as the referendum’s failure - which currently looms as a very likely prospect - will do nothing to help anyone except racists. As we’ve seen since 1999, losing referendums don’t simply pick themselves up off the mat. Even if ‘Yes’ wins, however, the Great Australian Bewilderment will simply move on to the next redoubt. (Look for statements like ‘How can Australians make a treaty with themselves?’)

Either way, there will be much said over the coming days and weeks about how history will judge us for the result. Perhaps the judgement we should fear most is also the simplest: You knew.

The opinion polls show a huge divide between Australians over 65 and those 45 or under. It's probably not much consolation but the Australia that I would like to see very much corresponds to the under 45 view of the world. I may not get to see it, but it is coming.